This week we look at some of the notable issues facing public schools in Washington as students and educators begin the new school year. The episode features different perspectives from education policy advocates and stakeholders, as well as the state superintendent.

We begin with the Washington Supreme Court’s ruling against the Wahkiakum School District’s constitutional challenge of the state’s school construction funding framework. The district has tried unsuccessfully to pass construction bonds in the rural county, which prevents Wahkiakum from tapping into the major pool of state funding reserved for school construction assistance. The lead attorney for the district, Tom Ahearne, was also lead attorney for the successful McCleary lawsuit which led to major changes in how the state funds public education, which the Washington Constitution describes as its “paramount duty.” The plaintiffs argued the cost of making necessary facility upgrades is out of reach because of the way school construction funding is structured in the state, which puts K-12 students from rural counties with lower per-capita incomes and much smaller tax bases at a major disadvantage compared to students in counties with larger populations and more economic development.

But the author of the lead opinion for the court, Justice Sheryl Gordon McCloud, wrote that the state constitution treats construction costs differently than other education costs and “requires the State and local school districts to share the responsibility for those school capital construction costs. For that reason, we hold that the constitution does not include capital construction costs within the category of “education” costs for which the State alone must make ‘ample provision.'”

“My reaction to the ruling is, I’m very disappointed, because what it does is, it condemns kids in the rural part of our state to a lousy education. Because you can’t have a good education in buildings that are falling apart, don’t have the wiring and cabling for things like, oh computers, and things like that,” said Ahearne. “If we want to have a system where we have two classes of people: the underclass and then the well educated class, this is a great ruling. But I don’t think that’s what our framers had mine when they’re writing our constitution.”

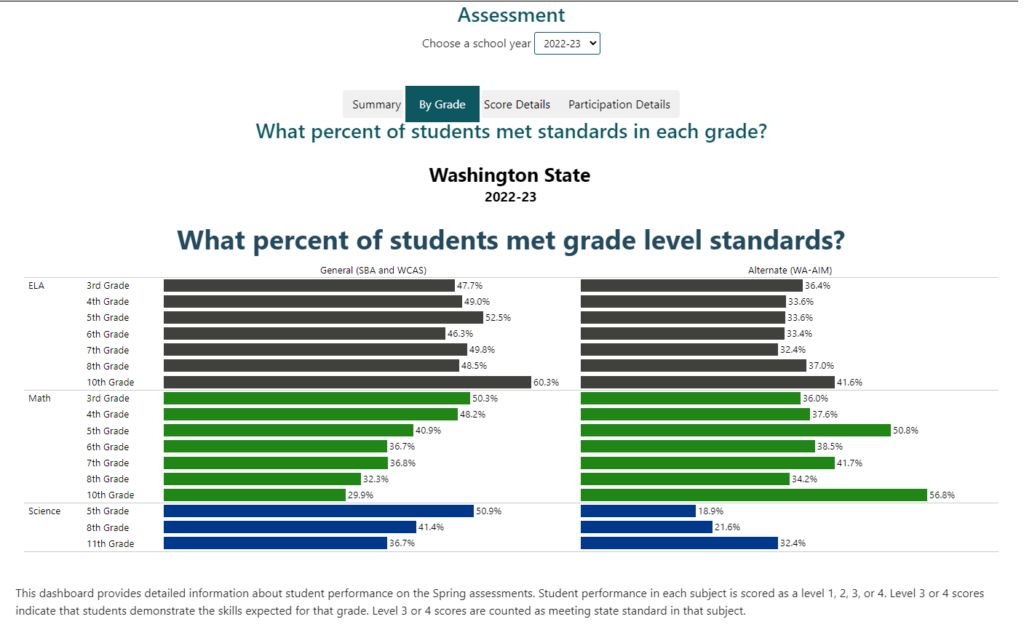

With the release of the spring 2023 state assessment scores, student test performance is another topic of discussion.

“I’m looking at these test scores and thinking these are alarm bells going off.”

Marguerite Roza, a Seattle based research professor and director of the Georgetown University Edunomics Lab

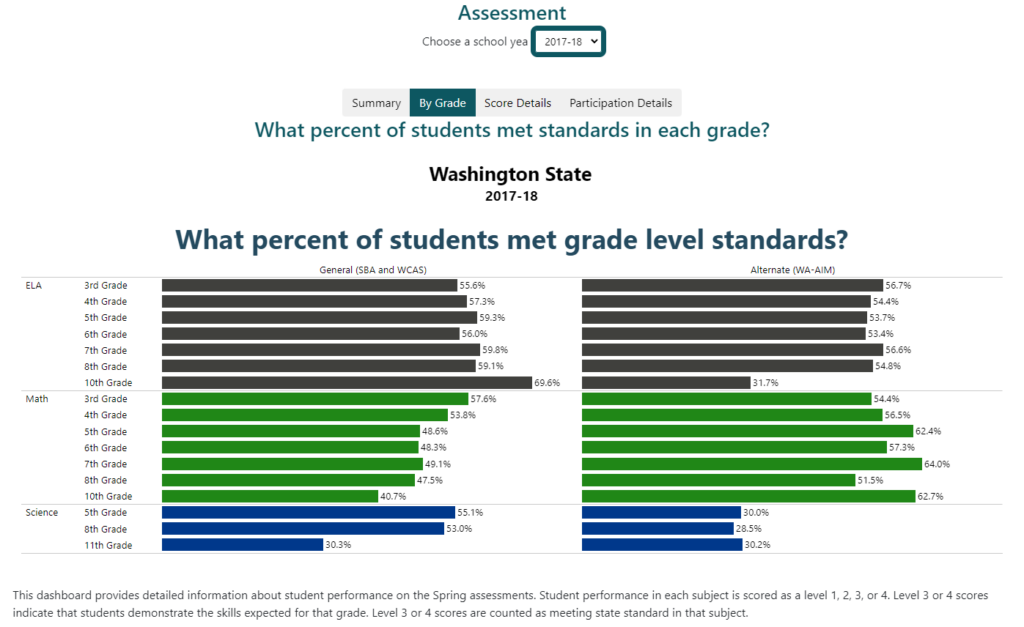

Marguerite Roza, a Seattle based research professor and director of the Georgetown University Edunomics Lab, said the recent test scores show students are still falling short of success rates from several years ago.

“We used to have 47% of our kids at standard in math in eighth grade. We’re down now to 32.3%. So those test scores don’t tell us everything a kid can do, but they do tell us something and they tell us something about the health of our system and whether or not it’s delivering value for kids,” said Roza. “It is signaling to us that fewer and fewer of our state’s kids can do math at grade level. In fact, when you see a 10% reduction in the percent of kids that can do math in our state, that means 100,000 fewer kids can do math at standard.”

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal addressed the state assessment scores during an extended question and answer session.

“They’re not pass fail tests. That’s been one of the really damaging narratives to student mental health and educator mental health for decades is the idea that this is a pass/fail test.”

Chris Reykdal, Washington Superintendent of Public Instruction

Reykdal noted that a number of universities no longer require applicants to submit standardized test scores for admission.

“The test itself is a pretty flawed device for even measuring whether kids are going to go to college or get into college, but it is a good indication of trend. Are we declining? Are we gaining? We clearly declined during COVID. We’re clearly gaining now,” said Reykdal. “I don’t ever use test scores as a single measure. And for any single student, the much better predictor is attendance, their time focused on their school, their pathway, the courses that they take. So what I take, the classes I take, the grades I get, and my persistence is a much better predictor than test scores.”

“What I would say is we want all students to be pushed further,” said Reykdal.

Test scores aside, Jacob Vela with the League of Education Voters said boosting support systems to address student mental health concerns should be a top priority for K-12 schools in Washington.

“That’s one constant thing that we’ve been hearing even before the pandemic, but especially since the pandemic started, is we really need to do better by students to provide the supports and services within the K-12 system to make sure that they feel like they can truly engage in learning,” said Vela. “You’re not going to be able to engage in learning until you really feel safe, supported in your school environment. So really providing the resources and supports and services and the structures to better resource empowered schools and districts to really better meet the needs of students is one of the most critical issues right now. And that’s an issue that’s echoed by pretty much everyone we talk to, student groups and teachers.”

“It’s a major challenge right now that we really do better as a state. We have dedicated a little additional funding to those areas in the last couple of years, but not enough to meet the need. And it’s going to take more than just resources to address the challenges. And we’re going to really have to make shifts in how we view and support students,” said Vela.