If the Washington State Legislature passes “Joel’s Law” this year — a bill that offers a way for families to appeal to the courts if their family members have been denied involuntary mental health commitment — it comes too late for the friends and family of Sheena Henderson of Spokane.

Sheena Henderson’s father, Gary Kennison, said the law might have been able to prevent his son-in-law, Chris Henderson, from coming to his wife’s place of work, where he fatally shot her and killed himself last July.

“We now have two children who are growing up without parents. Christopher, who committed this act, wasn’t a bad person,” Kennison said in a Monday morning hearing in the Senate Human Services, Mental Health & Housing committee.

Chris Henderson’s mental condition had been deteriorating in the months before the shooting, and he had been briefly hospitalized and his guns confiscated. But he was released from the hospital days before the shooting after assuring authorities he was no danger, and he collected his gun from the Spokane Police Department the day before the fatal shooting.

“There was no avenue whatsoever for us to go back and appeal that decision…. So I believe that Joel’s Law, had it been in place, it would have given me a tool to protect my daughter and she would have been here today,” Kennison said.

“Joel’s Law,” which is filed this year under Senate Bill 5269 and House Bill 1258, is named after Joel Reuter, who died in a shootout with Seattle police in 2013.

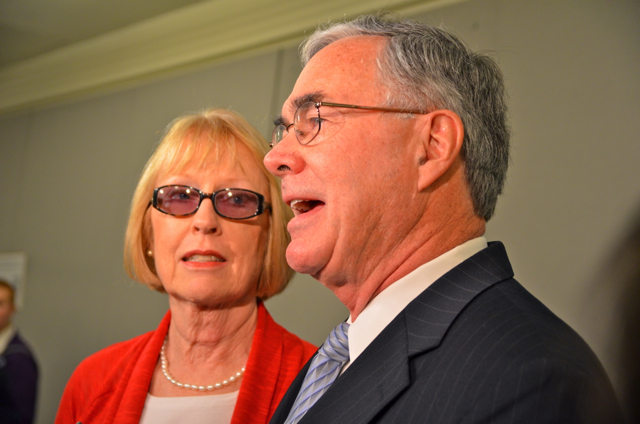

His parents, Doug and Nancy Reuter, came to Olympia from Texas to lobby the Washington State Legislature last year to pass the law. The bill passed the House unanimously, but was never brought to a floor vote in the Senate.

Joel Reuter had been treating bipolar disorder successfully for several years, but made a turn for the worse after starting chemotherapy for lymphoma. He died after shooting at police officers.

Joel’s family returned this session. Doug Reuter testified on Monday that he believes the designated mental health professionals are given too much leeway in making commitment decisions.

“They answer to nobody. The unilaterally decide who gets help and who does not get help,” Reuter said.

All families want is the ability to make an appeal, he said.

“This will not only provide an avenue for family members to have someone else — a judge — look at all the evidence to determine whether they are a danger to themselves or others. And it gives the (designated mental health professional) a chance to review their files all at the same time,” Reuter said.

Reuter also criticized the fiscal notes from last year, saying the costs are overestimated they assumed ongoing mental health treatment, when the bill only addresses commitment.

One change in this year’s bill is a provision to give the mental health professional 24 hours to respond to the family’s appeal before the appeal is heard by a judge.

However, Shankar Narayan, legislative director of the ACLU of Washington, expressed concern over the rights of those who would be detained against their will.

“This is a human being, a person who’s interests might be different from their family members,” said Narayan after the morning hearing.

Mike De Felice, a public defender who works with mental health cases in King County Civil Commitment Court, said the changes could tie up designated mental health professionals in court, when they should be in the community making assessments.

De Felice and Narayan both made the argument that the best place for the investment is in community mental health.

“Olympia needs to fund outpatient treatment in the community, and we can avoid them coming into involuntary treatment,” De Felice said.

Legislators in both chambers and both parties pledged to get the bill passed.

“I have been working very closely with the Reuter family, and other parents with a similar story, who were unable to get help for their son after numerous attempts,” said Sen. Steve O’Ban, R-Pierce County, who sponsored the bill in the Senate, in a prepared statement. O’Ban is also the chairman of the Senate Human Services, Mental Health & Housing committee.

Rep. Lillian Ortiz-Self, D-Mukilteo, said that since the issue was brought to the forefront last session, legislators have been hearing from families in similar situations.

“Across the state, legislators are now realizing that it’s becoming an epidemic,” Ortiz-Self said at a Monday afternoon press conference.

Doug Reuter said after the morning hearing that after the bill died in the Senate last year, he and his wife did not expect to return to Olympia for this session, but that Speaker Frank Chopp convinced them to return for another attempt to pass it.

“I thought everyone would forget Joel,” he said.